The Catholic Patriotic Minute: Charles Carroll

Catholics For Catholics Special Edition | July 4th, 2025

WATCH VIDEO below.

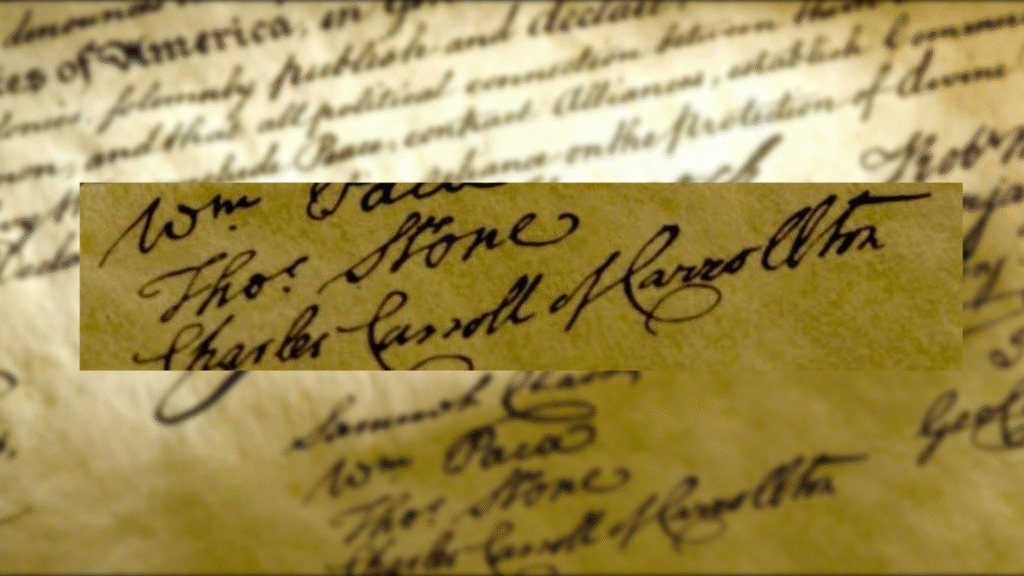

Charles Carroll, The One and Only Catholic Signer of the Declaration

Two hundred forty-nine years ago today, our founding fathers adopted the Declaration of Independence. Only one signer of the Declaration was Catholic. And this founder, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, would become an exemplar as a defender of religious liberty for Catholics in the newly-founded United States of America.

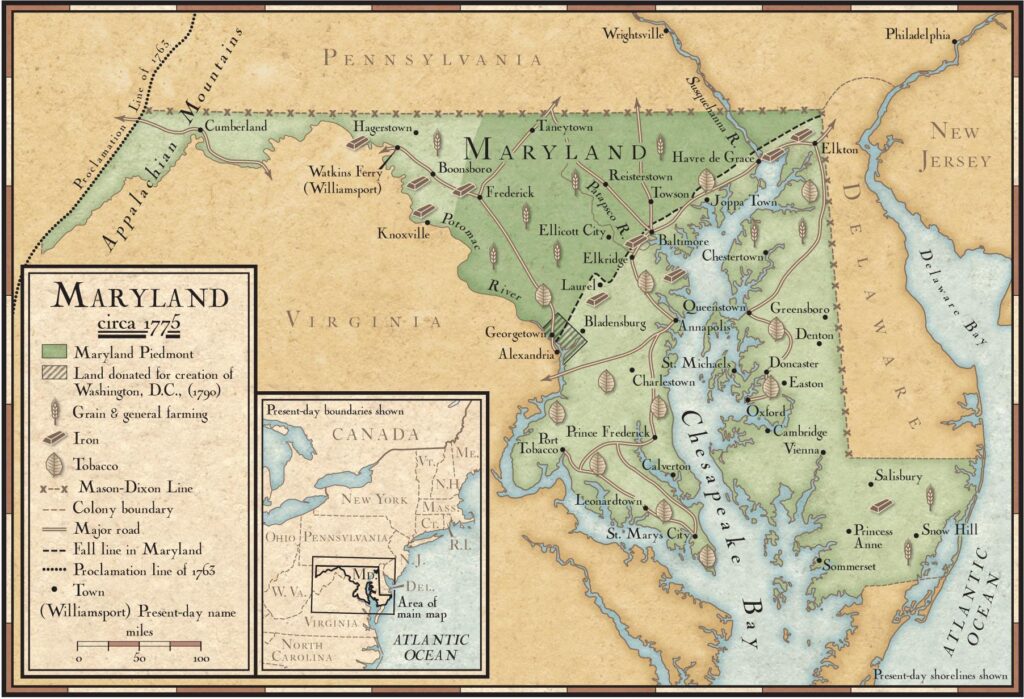

Born amidst persecution of Catholics in Maryland in 1737, Carroll did not get to enjoy the Maryland of 1634, the colony that harbored Roman Catholics fleeing from English oppression. Inspired by the “Glorious Revolution” that led to the last Catholic English Monarch, King James II, being deposed, Anglican minister John Coode led a rebellion against Lord Baltimore in 1689. Maryland’s government disregarded the Charter of 1632 and the Maryland Toleration Act of 1649, which gave Lord Baltimore the colony to be a refuge for English Catholics and allowed religious freedom for all who believed in Jesus Christ, respectively.

By the year 1718, Catholics could not practice their faith publicly. Priests could not celebrate Mass or evangelize. Parents could not teach their children Catholic doctrines; in fact, Catholic children could even be forcefully taken from their parents and placed somewhere else in order to be taught Protestant teachings. Catholic lawyers were not allowed in court. Catholics could not vote. All of these prohibitive laws would not only affect Carroll’s upbringing but move him to fight for religious freedom at the state and national level later on.

Carroll’s grandfather, Charles Carroll the Settler, brought his Irish family to the New World right before John Coode’s rebellion in 1688 to take refuge from Catholic persecution and to take up the role of Attorney General of Maryland. Because of the restrictions on Catholic education in Maryland, his father sent Carroll and his cousin John, the future first Catholic bishop in America, in 1749 to St. Omer, a Jesuit school of the liberal arts in France. At the age of thirteen, Carroll wrote to his father, “I can easily see the great affection you have for Me by sending me hear [sic] to a Colege [sic], where I may not only be a learned man, but also be advanced in piety & devotion.”(1) His master at St. Omer, Father John Jenison, confirms his pursuit of excellence and piety, when he asserted that Carroll was “the finest young man, in every respect, that ever enter’d the House” and that “[h]is application to His Book and Devotions was constant and unchangeable.” After studying common and civil law abroad, Carroll returned to Maryland and advocated for Catholics’ civil and religious rights in, at least, three historic ways.

Carroll’s first major defense of religious liberty for Catholics was in his “First Citizen” letters in 1773. With his pseudonym being First Citizen, Carroll debated Daniel Dulany– “Antilon” –in a renowned set of letters published in the Maryland Gazette. As historian Bradley J. Birzer has pointed out, one of the two main points of debate was “whether or not the Church of England should enjoy a legal monopoly in the colony.” In one letter, Dulany advised Carroll to “be quiet, and peaceable, and with all due application” since Carroll could not vote and be a part of public office as a Catholic. Rather than silencing himself, Carroll pushed back by posing the question of whether “these disabilities [prohibitive laws] extend so far, as to preclude [Catholics] from thinking and writing on matters merely of a political nature?” He called on Dulany, Protestants, and Catholics to consider toleration for all Christian religions as a reality. He attempted to find middle ground with Dulany by emphasizing in the letters that they could both be “averse to having a religion crammed down peoples’ throats as a proclamation” and that Carroll himself hates and despises “[k]naves, and bigots of all sects and denominations.”

Three years later, Carroll’s fight for Catholics’ liberty in Maryland advanced further when both Carroll and Samuel Chase convinced Marylanders to switch their position to supporting independence from Great Britain. Both men were selected as Maryland’s delegates for the Second Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence. Since his property was valued at a few million pounds at the time, Carroll’s signing the Declaration was an extreme risk because he pledged his life and fortune. But, Carroll sought religious liberty and civil liberty above all else. Later in life, he claimed, “[w]hen I signed the Declaration of Independence, I had in view not only our independence but the toleration of all sects, professing the Christian religion, and communicating to them all equal rights.”

Elected to be a member of the Maryland Convention and selected to be in a committee of seven to propose a state constitution in August 1776, Carroll helped secure religious liberty for his fellow Catholics. The committee proposed a clause that became the thirty-third provision of the Maryland Constitution: “[t]hat, as it is the duty of every man to worship God in such manner as he thinks most acceptable to him; all persons, professing the Christian religion, are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty; wherefore no person ought by any law to be molested in his person or estate on account of his religious persuasion or profession, or for his religious practice.” All prohibitive laws against Catholic Marylanders were no longer binding.

Before his death in 1832, Carroll funded and saw the completion of the original St. Mary’s Church, the first Catholic church in the city he grew up in, forbidden from practicing his faith. In the few days before his death, he reflected on his life: “I have lived to my ninety-sixth year. . . I have been blessed with great wealth, prosperity, and most of the good things which the world can bestow-public approbation, esteem, applause; but what I now look back on with the greatest satisfaction to myself is, that I have practiced the duties of my religion.” A priest, present in Carroll’s last few days, remembered his devotion to the Holy Eucharist that lasted till his last breath. The priest recounted, “At the moment of offering the Host [Carroll] leaned forward without opening his eyes, yet responsive to the word of the administration of the holy offering. It was done with so much intelligence and grace, that no one could doubt for a moment how fully his soul was alive to the act.”

When Carroll passed away, newspapers with headlines such as, “[a] great prophet in Israel hath fallen; the Last of the Romans has passed,” were distributed nationally. Not only would Carroll be known as the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, but he was also the last surviving signer of the founding document. His death marked the end of the founding generation. However, the cornerstone of Charles Carrol’s legacy is that he risked his life and livelihood to fight for the religious freedom of his fellow Catholics, out of a deep love for his God and Church.

Save and Share This Catholic Patriotic Minute!