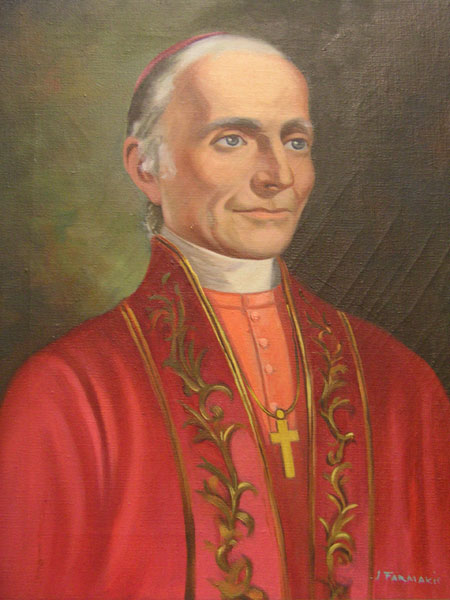

The Catholic Patriotic Minute #7: Bishop Simon Bruté

Catholics For Catholics Special Edition | August 18th, 2025

The Life of Servant of God Bishop Simon Bruté: A Lesson in Surrendering to God’s Will

On August 19, 1839, during a service for the repose of Simon Bruté’s soul, at Mount St. Mary’s College, the deceased’s friend and college’s president, Father John McCaffrey, reflected on the French missionary’s life as he neared death, “[w]hen unable to walk or stand, he would at least sit up, and write to any whom he could hope to benefit by his correspondence; and to those around him he would speak on pious subjects, such as the love of God, conformity to His holy will, or devotion to the Blessed Virgin, with the unction of a saint, and the ardour of a seraph. . . ‘The will of God be done’ was the constant language of his lips, as it was the abiding sentiment of his heart.” Sharing his love for his Heavenly Father was a practice that Simon practiced from his childhood all the way to his deathbed. His constant pursuit of submitting to God’s Will put him on the path towards sainthood.

Born on March 20, 1779, Simon was born in Rennes, a city in Brittany, France. Simon’s childhood was marked heavily by both the French Revolution and his Catholic faith. The French commoners of the Constituent Assembly, who led the Revolution against the French elite, declared their efforts to take control of the Catholic Church, through the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Most priests faithful to the Magisterium were executed until the year 1794, and even after then they were still imprisoned or deported.

In light of the persecutions of Catholics, Simon’s devout mother, Madame Bruté, hid two Catholic priests in her home, risking the safety of her family. Simon’s notes and sketches from his childhood revealed his own involvement. His sketch of the Cathedral of Rennes was accompanied with his memory of attending Mass there until the Church was taken and used as a prison for Catholic priests who would not abandon their perpetual vows in the early 1790’s. Simon wrote that he “visited them twice while they were confined there, disguised as a baker’s boy, a big bread basket on my head.” Others remembered how Simon would bring the Eucharist from a priest-in-hiding to the imprisoned priests.

Not only did Simon receive the Sacraments from the priest-in-hiding, but he also received an education from them. Although Simon helped out in his mother’s printing business, he sought out a career in medicine in Paris at the age of twenty. Because Paris was known as a city of immorality, especially after the Revolution, Simon’s mother advised him to live out his Catholic faith, read the Bible and the writings of Saint Francis de Sales, and to find a confessor. There, Simon attended the College of Medicine, where there were strong anti-Catholic sentiments. Yet, with the guidance of a priest and a few of his peers, Simon persevered. In fact, his written thesis included his proclamation of the Catholic faith. He received the Corvisart Prize, an award for the most outstanding student at his medical school, and graduated in 1802. The French government offered Simon the position of physician to the First Dispensary, Paris’s main medical center, most likely due to the suggestion of the First Consul of France Napoleon Bonaparte, as Simon’s success caught his eye. But, Simon turned down this appointment. Rather than continuing with his plan of becoming a physician, Simon accepted God’s call for him to pursue the priesthood.

Despite the pressure from his mother and his peers to remain a physician, Simon started his private religious studies until seminaries were reopened in 1804, when he began at the Seminary of Saint Sulpice in Paris at the age of twenty-five. On June 10, 1808, Bruté was ordained a priest and joined the Sulpician order, which cultivated the mission of guiding seminarians toward the priesthood. While he taught at the seminary in Rennes, Father Bruté was offered a position in the imperial chapel by Bonaparte, but he turned down an offer from the First Consul again. He felt called to be a missionary in India or China. However, Father Bruté was sent West, not East.

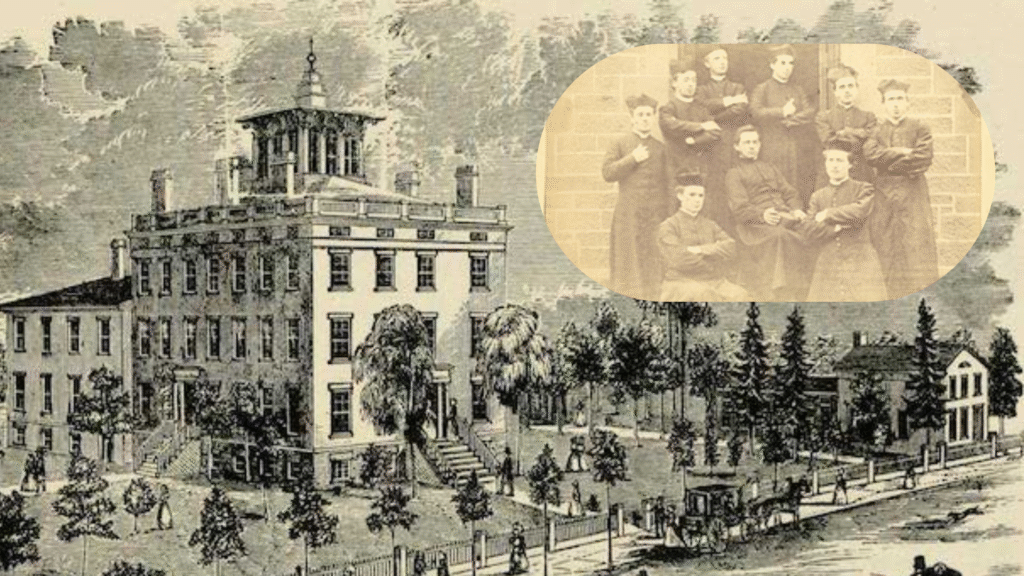

Father Bruté met Bishop-elect Benedict Joseph Flaget of Bardstown, Kentucky, who interested Bruté in missionary work in the States. He wrote to his friends, “[i]t is at this moment that I have need of my friends before the Lord…I depart for the American missions. My spiritual directors have been unanimous in their opinion. The Bishop consented with a readiness that confirmed me in the hope that it is a call from Providence.” Exactly two years after his ordination, Father Bruté sailed across the Atlantic to the States. First, he was assigned to teach moral theology at a college and seminary in Baltimore, Maryland, and then two years later, he was sent to teach at Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg, Maryland. Father Bruté was faced with hardship early on during his mission. He could not speak or understand English well. His library–his most prized possession–did not follow him West right away. He returned to France and brought it back to the West in 1815. And, he could not forget his personal calling to be a missionary in the East.

At St. Mary’s College, as Archbishop Buechlin would later write of Bruté, “[b]ecause of the circumstances and developing culture in America, [Bruté] had deep convictions about the need of solid philosophical and theological formation for the future priests. He was considered an exemplary priest, noted for his holiness and for his pastoral dedication as well as for his theological expertise.” His teaching improved, as his new friend, Elizabeth Ann Seton, helped him learn more English. The future saint had moved to Emmitsburg and founded the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s in 1809. After meeting in 1812, Bruté became her spiritual advisor.

Between 1815-1818, Father Bruté was assigned the position of president of St. Mary’s College in Baltimore. He was one of the primary theological consultants during the Councils of Baltimore, where he expressed his worry that Catholic communities in the New World were not all theologically sound. Father Bruté’s reputation reached the elites of the States, as John Quincy Adams reportedly claimed that Father Bruté was the most learned man in America.

During this period, his letters with Seton revealed his lonely disposition, as he had left his community in Emmitsburg. His friendship with Seton helped him find peace in God’s Will. Once, she wrote to him, “[y]our restless thoughts strike me to the soul. You make the lesson of the grace of the moment so very plain to me, I owe you perhaps my very salvation by the faults and sins it has saved me from; yet physician you will not heal yourself … . If our God does indeed graciously [destined] you for China, will He not, seeing the overflowing of your boiling heart for it, open an evident door?” They remained close friends until her death in 1821. He administered Communion to Seton in her last fifteen minutes of earthly life. Later, Father Bruté noted, “[n]o soul has so forcibly excited m[y own soul] to see what it is to be the priest of my God.”

At the age of fifty-four, Father Bruté was nominated to be a bishop in the New World. Father Bruté resisted becoming a bishop because of his health problems and his inability to handle administrative work. He even wrote to one of the bishops, who nominated him, “[y]ou saw me avoid all the banquets during the Council. I have acquired none of the American manners and am incapable after all of acquiring them. I am always with my books in my corner in the third story, or at the Sisters.” He also wrote, “having lost my teeth at an early age, and having neglected myself more and more in this regard, I am incapable of speaking in public.” Despite his protests, Father Bruté was named the first bishop of the Diocese of Vincennes, which covered Indiana and a significant section of Illinois. Once all of his bishop friends from the West told Father Bruté that he must accept it, Father Bruté finally submitted to God’s calling. On a steamboat, he left Maryland for the Midwest with only two hundred and forty dollars and a gold watch. His only other possession, his library, would have to be sent to him later.

Bishop Simon Bruté was consecrated on October 26, 1834, the feast day of the apostles Simon and Jude. The following day, Bishop Bruté, wrote to his flock, “[u]nworthy as I am of so great an honour, and of myself unequal to the charge, my only trust is in God, and therefore earnestly calling for your prayers, that I may obtain His divine assistance, I come to be your chief pastor.” He dedicated his Dioceses of Vincennes to Our Lady and the cathedral to Saint Frances Xavier, as it would become the home for French, Irish, and German migrants. Bishop Bruté was faced with the tasks of much-needed spiritual formation of the French Catholics, who for the most part possessed faith but did not live it out well through the sacraments, as well as retrieving funding to improve their cathedral and to educate young men about the priesthood.

Having finally let go of his dream to be a missionary in India or China, Bishop Bruté fully embraced his mission in Indiana. In 1835, he visited his whole diocese on horseback, travelling over a thousand miles in spite of his health issues. He found that his flock needed more priests, and so the bishop left for Paris the same year. Having gained the admiration of the priests and seminarians in France because of his adventures in the New World, the bishop returned to his diocese with eight priests and twelve seminarians.

During his ministry in Indiana, Bishop Bruté wrote to another bishop, “[g]enerally my troubles are more on the surface and there is peace in the depth of my heart where dwells a pure and simple abandonment to God alone (emphasis added).” He met eternal peace, when he passed away on June 26, 1839, from tuberculosis. He had spent his last few days of life travelling to attend to his diocese, even though he could not even sit up straight on horseback from his illness. By 1839, the bishop left his diocese with twenty-five priests, twenty seminarians, twenty-seven active churches, two new religious communities, and schools for children and young adults. In September 2005, Archbishop Daniel M. Buechlin opened the cause of canonization for Servant of God Simon Bruté.

For more Catholic Patriotic Minutes, visit CATHOLICUSA.COM

Save and Share This Catholic Patriotic Minute!