The Catholic Patriotic Minute #19: Servant of God Walter Ciszek

Catholics For Catholics Special Edition | November 12th, 2025

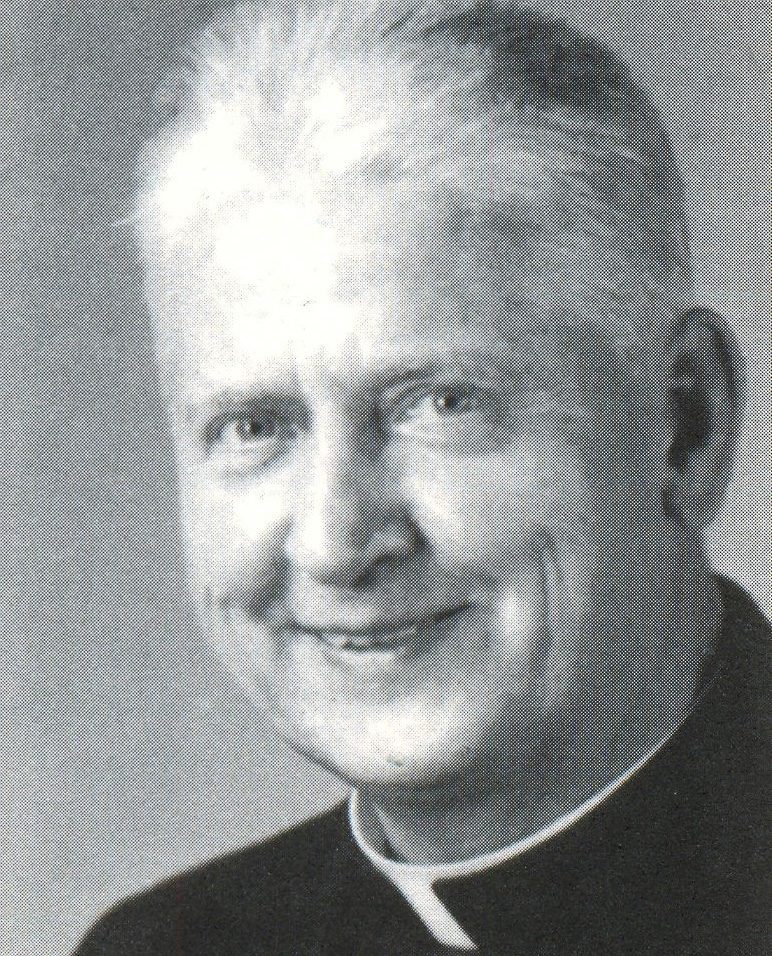

Servant of God Walter J. Ciszek: An American Priest and Prisoner in Soviet Russia

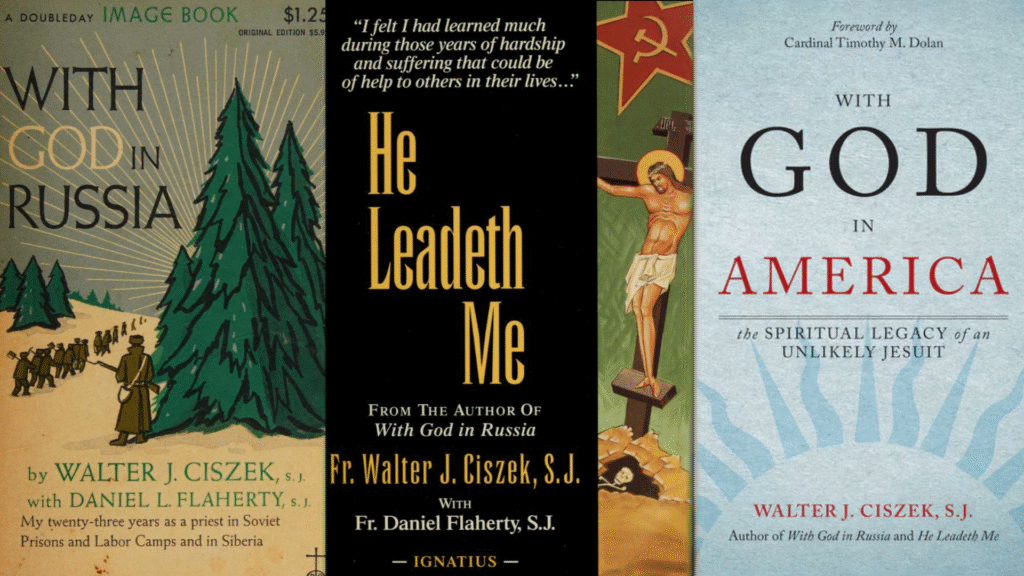

In 1938, an American priest, Father Walter Ciszek, was assigned to serve as a missionary priest in Poland. But, a year later, Germany and Soviet Russia invaded Poland, initiating the Second World War. Father Ciszek fled the invasion by escaping to Russia, only to be arrested and imprisoned by the Soviet Union for twenty-three years. For fifteen of the twenty-three, he was ruthlessly interrogated or forced to do hard labor in the Gulag. Father Ciszek attributed his survival solely to God’s providence.

On November 4, 1904, Walter Ciszek was born to a Polish family in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. In his 1964 memoir With God in Russia, Father Ciszek wrote of his childhood, “I was a bully, the leader of a gang, a street fighter – and most of the fights I picked on purpose, just for devilment, I had no use for school, except insofar as it had a playground where I could fight and wrestle or play sports.” Walter’s father even took him to the police, demanding they send Walter to a reform school. Father Ciszek attributed his toughness to his father and his understanding of his vocation to his mother. His father was utterly surprised that his son, a bully and street fighter, would want to be a priest. Father Ciszek wrote, “it must have been through my mother’s prayers and example that I made up my mind in the eighth grade, out of a clear blue sky, that I would be a priest.”

Soon after, Walter joined Sts. Cyril and Methodius Seminary in Orchard Lake, Michigan. Here, he struggled with piety being on display. In fact, he would pray in the chapel when no one was there. Even though he was a seminarian and not a gang member anymore, Walter still wanted to be tough. He would run five miles or swim in the freezing lake at the seminary every morning at 4:30. Determined to do “the hardest thing,” Walter would complete penitential acts like abstaining from meat for a year or only eating bread and water during Lent. Inspired by the life of Saint Stanislaus Kostka, who was a tough Pole that became a Jesuit priest, Walter began to wonder if he should enter the Society of Jesus. It would be difficult because it would add at least seven years of study to the three years Walter had remaining. But, this difficulty made becoming a Jesuit more appealing to Walter. Father Ciszek recounted, “I just prayed and fought with myself–and finally decided, since it was so hard, I would do it.”

In 1928, Walter joined the Jesuit Provincial in New York. A year later, Pope Pius XI sent a letter to all seminarians, asking for some to consider entering a new Russian center in Rome and preparing for missionary work in Russia. Walter moved to Rome, where he studied theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University as well as the Russian language. Here, he learned to celebrate Mass in the Byzantine Rite. By the time he was ordained in 1937, the Church could not send priests to Russia, so Father Ciszek was assigned to a Jesuit mission in Albertyn, Poland.

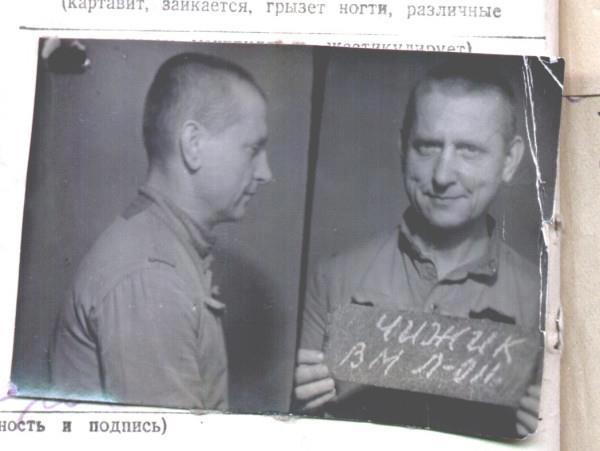

When both Germany and Russia invaded Poland in September 1939, Father Ciszek, in disguise as a worker, made his way into Russia with the aim of continuing his purpose of converting and saving souls. However, in June 1941, Father was arrested by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, under the suspicion that Father Ciszek was a Vatican spy.

From 1941 to 1945, the NKVD brutally interrogated and tortured Father Ciszek, constantly threatening execution. During these four years of purgatory, he lost his faith and hope in God. Rather than stubbornly holding on to “doing the hard thing” by himself, Father Ciszek immediately turned to prayer and meditated on Christ’s prayer to His Father in the Garden of Olives right before his crucifixion. Just as Christ surrendered his fear of suffering, Ciszek needed to surrender himself to God’s will. He described this surrender as “‘letting go,’ giving over totally [his] last effort or even any will to guide the reins of [his] own life.” When his interrogator told Father that he would be a Russian spy in the Vatican, Father Ciszek simply replied, “no.” Although the consequence was Siberia, Father felt completely at peace.

Sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor, Father Ciszek left Moscow for Siberia. After five years of no labor, shoveling coal for twelve to fifteen hours every day was definitely a hurdle for Father at first. Yet, he would write later, in his 1973 memoir He Leadeth Me, that this physical toil allowed him to pursue his own salvation. If salvation is carrying the cross of Christ, humans–as creatures of both body and soul–seek salvation with both. Father Ciszek explained, “Work was not a curse, even the brutish grunt work I was doing, but a way to God–and perhaps even a way to help others to God.” And, so he did.

Even in Siberia as a prisoner, Father Cizsek was able to continue his mission work, as he performed the Holy Sacraments in secret and served as a spiritual director for many. Although he had to suffer multiple interviews by the NKVD involving psychological warfare because he was a priest, Father Ciszek never stopped serving his flock, accepting each and every punishment. Alongside other priests, Father would say Mass while they took walks in the forests or while they pretended to read or chat. He began to imagine the trees in the forests as pillars in a cathedral. The priests would celebrate Mass for prisoners in storage shacks. For Father, nothing could stand in his way of saying the Mass daily for the prisoners and giving them the Eucharist.

When Father was asked by other prisoners why he worked so hard, they were not usually satisfied by Father’s answer, that his time in Soviet Russia was a part of God’s Will. Being a prisoner taught Cizsek that there is joy in sacrifice and pain. How? As Father wrote,“[s]uch suffering can only bring with it deep spiritual joy, for from its springs redemption and salvation, the ultimate victory over sin and further suffering and even death itself.”

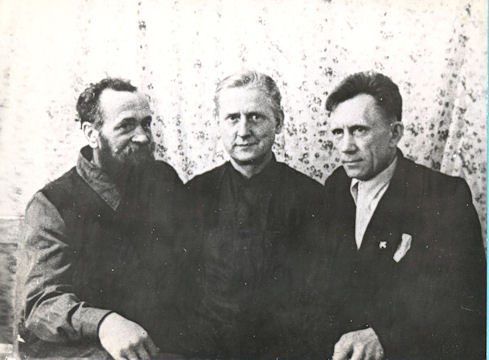

After serving fourteen years and nine months of his fifteen-year sentence, Father Cizsek was freed from his prisoner camp in 1955. However, it was a limited freedom, as the Russian government still limited where he could live and what occupations he could have. On the train to Norilsk, he reflected on this seemingly-new freedom and came to the conclusion that he never lost his freedom. He later wrote, “[t]he body can be confined but nothing can destroy the deepest freedom in man, the freedom of the soul, and the freedom of mind and will. . . Even in prison, a man can choose to do good or evil, to fight for survival or to despair, to serve God and others or to turn inward and selfish.”

From 1955 to 1963, Father Ciszek moved from Norilsk to Krasnoyarsk and then from Krasnoyarsk to Abakan because the KGB found out he was administering the Holy Sacraments to Catholics, something he was forbidden to do. In 1963, one month before John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the President negotiated for Father Ciszek and an American student to be traded for two Soviet spies. From 1963 until his death in 1984, Father Ciszek served at the John XXIII Center at Fordham University and wrote three memoirs. The cause for his canonization was opened in March 2012.

After being away from the United States for about thirty years, Father Ciszek was astounded at the state of religion in the States. He remarked, “[a]t first glance religion here seems almost a formality, an obligation that can be dispensed with if you have been out late the night before. . . I could not help being struck, thunderstruck, at this initial impression of indifference to religion in a country where there was nothing to restrain its open practice.” Let’s pray for the intercession of Servant of God Walter Ciszek, with the intention that American Catholics pray with complete abandonment to God, just as Father Ciszek did in the Gulag.

For more Catholic Patriotic Minutes, visit CATHOLICUSA.COM

Save and Share This Catholic Patriotic Minute!