The Catholic Patriotic Minute #33: Henry Adams

Catholics For Catholics Special Edition | February 16th, 2026

Henry Adams: Born a Unitarian, Died a Thomist

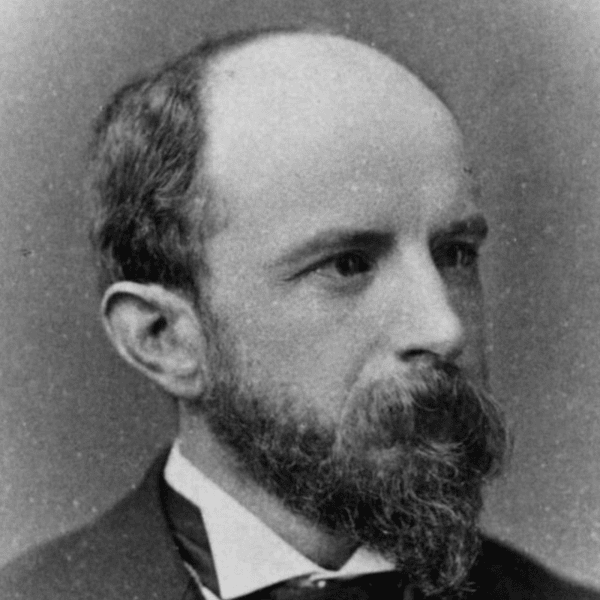

Apart of the Adams Dynasty, Henry was the great grandson of the Second President John Adams and the grandson of the Sixth President John Quincy Adams. Henry’s father was Charles Francis Adams. These three patriarchs in the Adams family all shared similar political ambitions. John, John Quincy, and Charles Francis were all U.S. diplomatic ministers to Great Britain at pivotal points in American history. After the Revolutionary War, John Adams secured the Treaty of Paris. Near the end of the War of 1812, John Quincy Adams negotiated the Treaty of Ghent. During the Civil War, Charles Francis Adams remained in London, with his son Henry as his secretary, to make sure Great Britain did not ally themselves with the Confederacy.

All three also shared their religious persuasion, Unitarianism–a popular religion in the United States of the nineteenth century that denied doctrines like the Holy Trinity and original sin and prioritized reason and science over faith. Even though he was baptized a Unitarian, Henry Adams diverted from his family in respect to religion, as well as political office.

Born on February 16, 1838, Henry grew up in Boston, Massachusetts. When looking back at his childhood, Adams considered his sickness of scarlet fever at the age of four to have permanently influenced not only his body but also his character. Scarlet fever made him short, and subsequently, Adams asserted, that his height gave him the characteristics of a “habit of doubt; of distrusting his own judgment and of totally rejecting the judgment of the world; the tendency to regard every question as open.” Henry did not prefer school, but he would live in his father’s library, studying Latin and reading mostly 18th-century historians and poetry.

Henry Adams considered himself to be a nineteenth-century man, provided with an eighteenth-century education, that lived his whole life confused about the twentieth century. He wrote, “What could become of such a hold of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when he should wake up to find himself required to play the game of the twentieth.” His old-school, liberal arts education made him surprised at the intellectual crisis of the United States leading up to the turn of the twentieth century. He was faced with “bear[ing] his own universe” and century–a century of innovations and revolutions.

After graduating from Harvard College in 1858, he went on a grand tour in Europe, as was tradition for men of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. From 1861 to 1868, Henry served as the secretary to his father, Charles Francis Adams, the minister to Great Britain, during the Civil War. Rather than pursuing political office as the Adams patriarchs had done, Henry first pursued journalism in Washington D.C. in 1868, publishing articles on D.C. corruption and even warnings about emerging inventions, such as the railroad. Then, in 1870, Adams became the professor of medieval history at Harvard. After seven years, Adams left Harvard because he disagreed with Harvard’s way of teaching history, through the lens of German progressive thought led by thinkers like Kant, Hegel, and Marx.

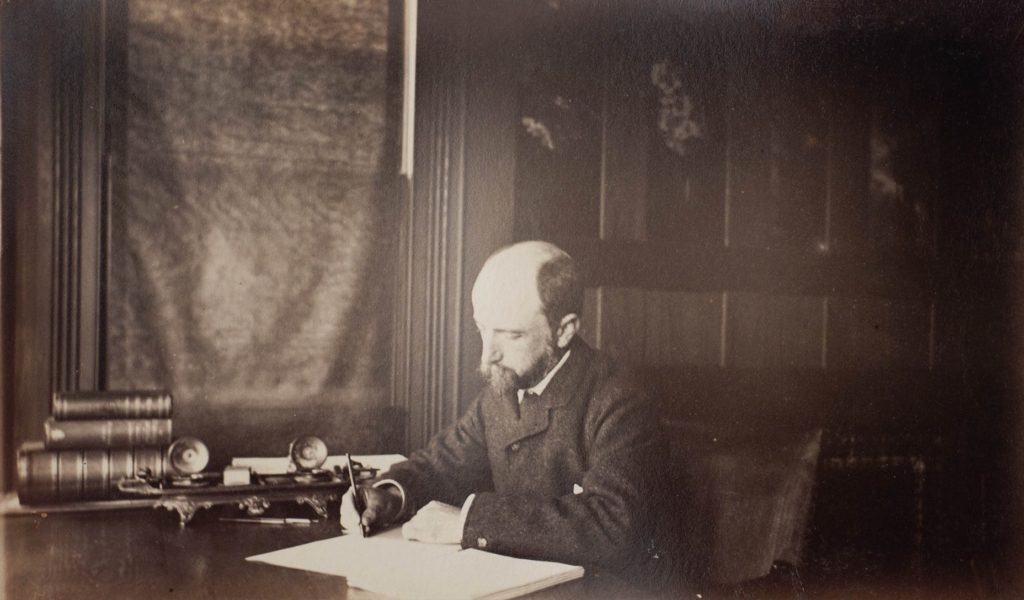

In 1872, Adams married Marian Hooper. They were never able to have children, but Henry “adopted” his nieces, nephews, and others, whom he would refer to affectionately as his nephews and nieces-in-wish. They moved back to Washington D.C. in 1877 because he was commission- ed to write a biography on the secretary to Thomas Jefferson, and wrote his book History of the United States, During the Administration of Jefferson and Madison. Rather than becoming a politician, Adams enjoyed being friends with one. His best friend, John Hay, became the U.S. minister to Great Britain and eventually the Secretary of State in the administrations of Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt. The Adams and Hay families lived in adjacent homes across the street from the White House, now known as the Hay-Adams Hotel. They would walk about the capitol, and Adams would advise Hay on matters of foreign policy.

However, the year 1885 introduced a dark chapter into Adams’s life. After the death of her father, his wife Marian committed suicide, and subsequently so did her siblings. Henry took care of his five nieces thereafter, teaching them and taking them to Europe. After Marian’s death, he spent the majority of his life traveling and writing. Adams wrote two novels, Democracy and Esther, both of which were published posthumously. His most well-known work, The Education of Henry Adams: An Autobiography, was privately published in 1907 and later publicly published after his death. His autobiography would win the Pulitzer Prize and became the Penguin Modern Library’s #1 Nonfiction Book of the Twentieth Century. His book, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, his study of the twelfth century, medieval churches, and Thomas Aquinas, was privately published in 1904 and publicly published in 1913.

For a man who struggled with the “game of the twentieth [century],” the question he always asked himself was–Why is the United States of the twentieth century falling, just as Rome did? His autobiography asked this question, and Adams answered his own question in his book Mont Saint Michel and Chartres. In his autobiography, Adams explained that people venerate one of two objects–either materialism or spiritualism–that is, the Dynamo and the Virgin respectively. While the Dynamo–the generator of electricity on display at the 1900 Paris Exposition–embodies material forces, through science and technology, the Virgin–the Blessed Mother–embodies spiritual forces, by way of contemplation of the divine and natural, and is the controller of the material forces. In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Adams claimed that the antidote to the twentieth century’s crisis involves both the Blessed Mother and Thomas Aquinas.

In his autobiography, Adams reflects on his visit to Rome in 1860. In 1860, Rome had not yet been conquered by Northern and Southern Italy. However, by 1870, the Vatican had been exiled across the Tiber, and Rome was crowned the capital of the Italian modern-state. Adams wrote, “Rome before 1870 was seductive beyond resistance.” Rome before authoritarianism worshiped the Virgin, not the Dynamo. Adams recounted, “no one, priest or politician, could honestly read in the ruins of Rome any other certain lesson that they were evidence of the just judgements of an outraged God against all the doings of man.” Why did Rome fall? Rome taught Adams that all civilizations, even Rome, fall because there is vice and virtue in every civilization. Rome made Adams understand that the answer, to why the United States was falling, is original sin.

For Adams, Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica provided a solution to the intellectual crisis of the twentieth century, as progressivism and totalitarianism caused havoc. In his book Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Adams agreed with Aquinas that man is spiritual and physical, rational and free. God created all mankind in one act. God “filled the Church by uniting Mind And Matter in man, or man’s soul, giving to Humanity a Free Will that rose, like the fleche, to heaven.” Man is free but not without limits as man is not only responsible for himself. Adams quoted Thomas, “[w]e are masters of our acts. . . in the sense that we can choose such and such a thing; now, we have not to choose our end, but the means that relate to it.” Man has limited freedom to encounter his immortal end. Adams understood the chaos of the twentieth century was due to the loss of the Thomistic and medieval understanding of man as rational and free.

About nine days after the Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, Henry Adams suffered a stroke. What is the correlation? Well, Adams was supposed to travel on the Titanic’s return voyage to Paris. After hearing news of the Titanic, he heard news of the sinking of the Republican Party the same week. Theodore Roosevelt had opposed the Republican nominee William Taft and would later launch his Progressive Party Platform, splitting the Republican vote and allowing for Woodrow Wilson to become president. Struck by these two tragedies, Adams’s stroke left him paralyzed and blind for a month. Once he recovered even though his sight was never fully restored, he hired a secretary and nurse-companion Aileen Tone, a Roman Catholic.

Aileen introduced him to Father Cyril Sigourney Fay, a well-known priest that befriended and even converted quite a few among the New England elite. Adams formed a strong friendship with Father Fay and once wrote of him, “delightful Father Fay who has an Irish love.

for the 12th century.” As Adams drew closer to the end of his life, his eighteenth-century self honored the Virgin, and he contended with Catholicism. In one letter, he mentioned that two of his antidotes for insomnia were songs to the Virgin and conversations about the Holy Trinity. In another letter, he wrote, “As far as possible I do nothing but talk about the Council of Trent with Father Fay, and the Day of Judgment with Aileen.” But, once Father Fay introduced more Catholics into Adams’s circle such as Arthur Balfour, Henri Bergson, Shane Leslie, and Cecil Chesterton, Adams found most modern Catholics to hold more modern philosophies, rather than the medieval Thomistic understanding of the world that Adams considered good and true.

Father Fay left for Rome quickly a month before Adams died on March 27, 1918. Although Henry Adams never made the final leap across the Tiber to Rome, he began his life as a Unitarian and ended his life devoted to the Blessed Mother. Because of Thomas Aquinas, Adams was finally able to understand America in the twentieth century as a nation that needed to cast her eyes once again on the Virgin.

For more Catholic Patriotic Minutes, visit CATHOLICUSA.COM

Save and Share This Catholic Patriotic Minute!